I have had the immense good fortune to spend this year as one of the 2019 AHRC/BBC New Generation Thinkers with nine fabulous early career researchers from across the UK humanities. The year’s culmination was to be our cohort recording an episode of BBC Radio 3’s The Essay at the 2020 Hay Festival… which obviously didn’t go ahead (boo). So the ten of us have recorded our Essays from bedrooms and basements and cupboards–on everything from techno music and race, to health and domestic work, to dams and geopolitics. Check us out here for the next few months.

My Essay, Facing Facts, is available to listen to now, and will be broadcast on Tuesday July 7 at 22:45. This is a short post to provide some links and references for anyone who wants to follow them up, and to outline some more on metoposcopsy: the secrets of fortune to be read in the forehead.

The Essay gives a snapshot of some of my current research into facial disfigurement in early modern Britain, and especially the level to which people experienced significant facial differences as disabling (meaning that they affected their capacity to fully engage with their communities, or earn a living, or experienced what we might understand as prejudice). I talk in particular about the Welsh prophet Arise Evans (1607-c.1665), who sought out Charles II to touch his nose in the belief that the king could cure an unpleasant swelling there. A long article about Arise is under review, but in the meantime I have an open access paper on treating facial wounds you might find interesting.

The other thing I wanted to share here was a link to Girolamo Cardano’s (1501-1576) Metoposcopia. As I mention in the Essay, the whole thing is available on Google Books. This is in Latin, but Google Translate will give you the jist if you spot your own forehead in this mix and want to know whether that mole is good news.

Others might like to look at a seventeenth-century English treatise on physiognomy and metoposcopy, such as Richard Saunders‘ (1613–1675) Physiognomie and Chiromancie, Metoposcopie (1653). Saunders was a medical practitioner and astrologer of some repute, though the books are based almost entirely on other works. He published a slightly enlarged edition of Physiognomie in 1671, and then smaller pocket versions focussing on palmestry.

The 1671 edition is available online. The first book covers hands (chiromancy), while the second (p.161) takes on faces and dreams (‘oneirocracy’ here, but more frequently oneirocriticism).

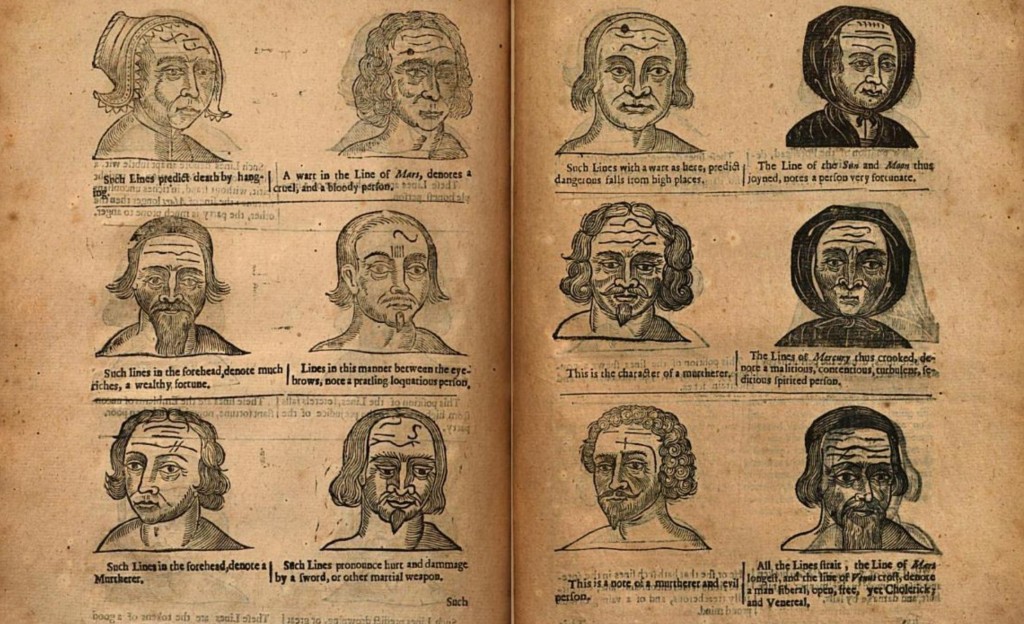

Lines on the forehead correspond to planets. The line closest to the hairline links to Saturn, then Jupiter, and so on (p. 212). Warts and moles provide further clues of fate, and Saunders includes a full-body map of moles and their significations. The faces are a mix of men and women, and while most don’t bode well, there are a few positive forehead fortunes at play.

We see a selection here including marks denoting a murderer, riches, death by hanging, a malicious and contentious person, falls from high places, good fortune, and loquaciousness.

One of the most interesting aspects of Saunders’ listings is the recognition that many qualities are double-edged swords: someone who is ‘open’ and ‘liberal’ will also therefore be ‘Venereal’ (sexually free); a man of genius in many things will therefore be unstable; while another whose lines denote “a good wit, most honest, approved and commendable moralities and conditions, nothing of fraud, or dissimulation” is therefore “too plain and honest to thrive, without a miracle”.

Even this text based on firm readings is therefore open to the vicissitudes of fortune, and the ambiguities of the face. It’s a good reminder to those who are today pushing for increased use of facial recognition (there’s an active legal case in South Wales this week), including some scientists who argue that it can predict criminality. Given the confirmed racial and gender biases of this technology, it is fair to say that digging through historical books that attribute or fates to the planets is probably a better bet.